Open vs Secret ballot system

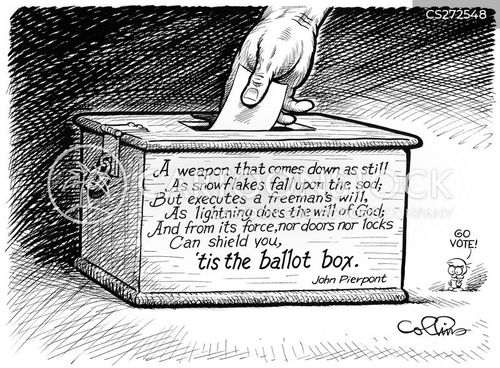

Introduction

Democracy has metamorphosed into complex systems of representative politics. The grundnorm or basic norm for any democratic polity is the impartial and free exercise of “consent” or choice. The unravelling in Gujarat on Wednesday raises significant questions in this respect.

The Congress was able to joust its way into the Rajya Sabha by giving Ahmed Patel his fifth term as an MP from Gujarat. However, the real fight was not in the House but outside it. With an order from the Election Commission, the Congress was able to invalidate two votes cast against Patel. The controversy ensued when two electors from the Congress cast their ballots for Balwantsinh Rajput and showed the same to Amit Shah.

As per the Conduct of Election Rules 1961, the procedure laid down for the Rajya Sabha elections calls for a ballot-in-secret. Secrecy under Rule 39A mandates that the elector cannot declare his ballot to anyone; any deviation results in the invalidation of the ballot by the presiding officer. But Rule 39A seems to be amiss of the grundnorm of a secret ballot.

Argument in favour in secret ballot

All electoral polling, either for the presidency, vice-presidency, Parliament, or state assemblies, is, in essence, a secret ballot. However, there are two means of executing such ends: The duty-based measure and the rights-based measure

- The rights-based measure provides the voter the right to keep his vote a secret. Such a right creates a correlative duty on the election authorities to afford voting facilities and procedures that do not disclose the vote. But the voter can choose to not opt for secrecy. The voter is given legal anonymity for the vote he casts, but he may choose to claim authorship over the same.

- The duty-based measure imposes secrecy as a statutory duty not only on the election authorities but also on the voter. The voter even by his consent cannot declare his choice; doing so would invalidate his vote.

Argument in favour in secret ballot

- Secrecy aims to protect the vote as it affords the right to the voter to keep silent over the choice of candidate.

- Mandatory nondisclosure of the vote presses upon the need that the voter should not be given an option to declare his vote because the flexibility would allow others to pressure him informally into declaring his choice

Limitation

- Rule 39A creates secrecy in the nature of a duty-based measure, which creates pragmatic absurdities that weaken electoral practice.

- Rule 39AA of the Conduct of Election Rules defeats this purpose. It mandates that an elector belonging to a political party must declare his vote to the party agent, if the political party has issued a whip regarding the vote. Refusing to do so is a violation of the election procedure and the vote stands invalidated.

- Rule 39A applies only while the election process is underway. There is nothing in the Conduct of Election Rules or the Representation of People’s Act which prohibits a voter from declaring his vote after the process is completed.

- Rule 39AA creates a party hegemony that assails the democratic consent of the elector. This allows for internal voter intimidation by parties. In such a case, it makes little sense to curtail the voluntary declaration outside the immediate party affiliation; rather it can be argued that a universal declaration eases the political pressure that an elector might face.

- This scheme lacks procedural merit because it cannot control the behaviour of the elector outside the ballot box. Therefore, the scheme of duty-based secrecy fails.

Essentially, all non-independent electors would have to disclose their choice in a secret ballot. It is essential as electors were resorting to cross voting under the garb of conscience voting, flouting party discipline in the name of secrecy of voting.

Ballot secrecy should be guided by the episteme of “consent” or choice; the means to adopt should be the rights-based measure.

Rule 39AA says that a voter may show his/her marked ballot paper to the authorised representative of his/her political party before dropping it into the ballot box. The question of law which cropped up was whether this kind of an ‘open’ election process had any secrecy of vote involved at all. Is it a violation of secrecy if a voter shows his/her marked vote to anyone other than the authorised representative concerned?

However, Rule 39AA is silent on who would be the authorised representative for a rebel MLA. Is it still the authorised agent of the party he/she has rebelled against or is it the representative of the political party he/she has voted for? Or does a rebel MLA enjoy the same status as that of an independent MLA?

References

The Indian Express

The Hindu

References

The Indian Express

The Hindu

Comments

Post a Comment